Why They Suck So Much

The lecture last week, however, was unique, since people kept coming to the special auditorium that is used for guest talks and academic ceremonies at the UL. It was filling up almost to the bursting point, so the whole show had to be moved to their Arts Building’s biggest auditorium which went full quickly, too. “Welcome to an experience only Slavoj Zizek has at our university,” said one of my colleagues, alluding to the city’s most famous academic, who obviously lectures there himself. I felt really flattered by people’s interest and leap of faith in me and, after having talked for almost an hour, I was punctured with questions by the great audience, among whom I could see what was left of Ljubljana’s Goth scene.

I am not telling this out of vanity, but to illustrate the fact that vampires don’t cease to appeal to young and not so young people. They obviously speak to them as a modern myth, and that is exactly what I am investigating as a scholar, among other things. It is interesting to find out, for instance, whether a central finding by US anthropologist Norinne Dresser is also valid for Europe: “The 3 major attractions of the vampire are totally compatible with American ideals of power, sex, and immortality. [...] It appears that American vampires are perfectly suited to this culture. They reflect those values which many Americans hold dear. They like to succeed. They always get the girl.”

At this stage, it’s time for my personal WTH question (which I usually get while making the acquaintance of somebody). That icebreaker comes in several versions and usually goes (roughly): “Why the hell would a serious (= Trinity) academic deal with such nonsense? Isn’t that just a waste of time?”

No, it is not, I keep answering patiently, since what I am doing with (and to) vampires is a kind of cultural history against the grain, not making the European Enlightenment and secularization its point of departure, but those irrational challenges and reactions to it; one of them being vampirism, in particular between 1732 and 1755, when quite a few leading intellectuals such as Voltaire and Gerard van Swieten would discuss this odd phenomenon. Myself, I read the vampire as a historical ‘mask of the Other’ that emerges in every era in a very special way (if you think of werewolves, witches, or aliens, just to name a few competitors of the undead bloodsucker).

When I say this to people, there usually comes the personal question: “So what draws you to vampires?” Well, in my early teenage days I started reading fantasy and horror tales as many kids did in my generation, since there was – among many other things – an excellent new German H.P. Lovecraft translation available by an outstanding Austrian poet, H.C. Artmann. I got in contact with the virus of the literary fantastic – which, as I can see now, helped me to cope with my father’s early death (and to this day, people suffering from a biographical trauma of sorts obviously find solace in this kind of genre literature).

Later, when I was done with my undergraduate years at the University of Vienna, Austria, I thought about starting a PhD on the literary history of vampires in the German-speaking world since there was almost nothing written about it. My to-be supervisor, one of the country’s most renowned literary historians, however stopped me by asking: “Do you want to be a scholar or a freak, Clemens?” Of course this was meant as a rhetorical question, so I dropped the topic for a while, but kept writing about it on the side (and smuggled one vampiric chapter into my doctoral thesis). Particularly in our part of the world, my supervisor had a point indeed: vampires (who cannot move over thresholds without being invited) pose a serious threat to academic careers.

Ever since, Trinity has proven to be a perfect place for research into the literary and cinematographic fantastic. With its expertise in gothic and horror studies at the School of English, for instance, or with our outgoing faculty dean and many other dear colleagues, it has to be said that we are a perfect stamping ground for monsters. And vampires don’t cease to amaze me – even when zombies are becoming the archetypical monster of the 21st century, as they say.

The 20 Best Vampire Movies (according to Clemens...)

- Alfredson T., Let the Right One In (Sweden, 2009)

- Almereyda M., Nadja (USA, 1994)

- Amirpour A.L., A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (USA/Iran, 2014)

- Bekmambetov T., Night Watch (Russia, 2004)

- Brooks M., Dead and Loving It (USA/France, 1995)

- Browning T., Dracula (USA, 1931)

- Clement J./ Waititi T., What We Do in the Shadows (New Zealand, 2014)

- Coppola, F.F., Bram Stoker's Dracula (USA, 1992)

- Dreyer C.Th., Vampyr (Germany/France, 1932)

- Gibson A., Dracula A.D. 1972 (UK, 1972)

- Herzog W., Nosferatu the Vampire (remake, Germany 1979)

- Jarmusch J., Only Lovers Left Alive (USA, 2013)

- Jordan N., Interview with the Vampire (USA, 1994)

- Jordan N., Byzantium (Ireland/UK/US, 2012)

- Murnau F.W., Nosferatu (Germany, 1922)

- Park Chan-Wook, Thirst (South Korea, 2009)

- Schumacher J., The Lost Boys (USA, 1987)

- Scott T., The Hunger (UK/USA, 1983)

- Tarantino Q., From Dusk till Dawn 1 (USA, 1996)

- Vadim R., Blood & Roses (France/Italy, 1960)

Clemens Ruthner

Dr Clemens Ruthner has been with the Department of Germanic Studies in the School of Languages, Literatures and Cultural Studies since 2008. He teaches in the fields of Germanophone literatures, German cultural history, and Central European Studies.

His other research focusses on Austrian literature and culture, the late Habsburg Monarchy, and cultural theory.

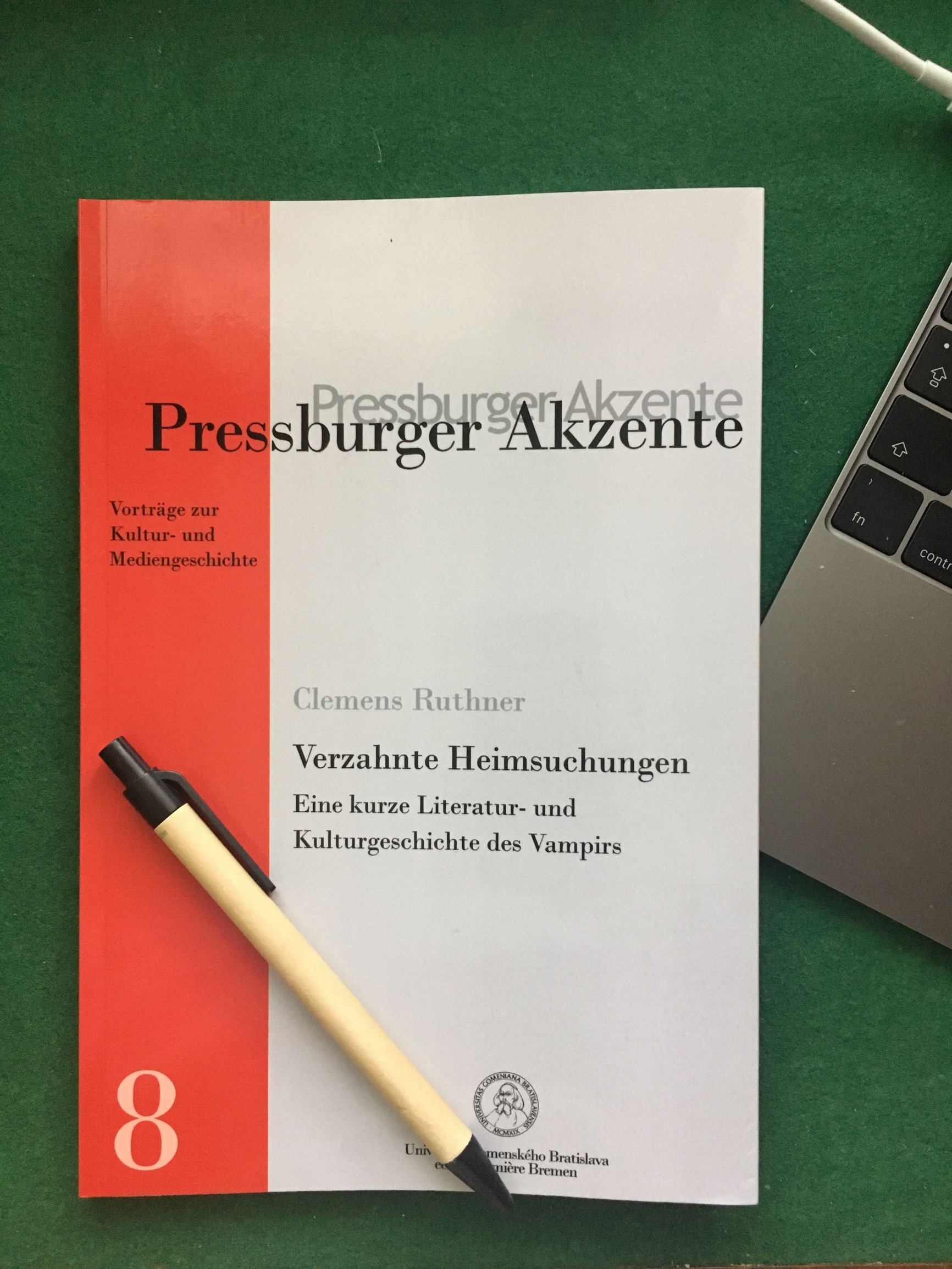

In 2019, his book Verzahnte Heimsuchungen (‘Toothed Haunting’, a literary and cultural history of vampirism) was published by Edition Lumière in Bremen, Germany. An extended English translation is in the making.

Profile picture (c) Isabel Thomas / kiyhuri photography