Between the Lines: Max McGuinness

When did you first come up with the idea for the book?

When did you first come up with the idea for the book?

My interest in connections between nineteenth-century French literature and journalism started when I was an undergraduate at Oxford University. I had to write a tutorial essay about Charles Baudelaire’s prose poetry and was struggling—late at night—to find something to say, so I started looking at the footnotes and discovered that most of his prose poems had originally been published in newspapers. Those journalistic origins help explain why the poet’s frustrations with journalism are a recurring theme in the prose poems themselves. At one point, he even bemoans his “cursed editor”.

I also realized I could consult original versions of these newspapers on the French National Library’s online portal, Gallica. Being able to read newspapers from 150 years ago at the click of a button came as a revelation that opened up a whole world of everyday literary-journalistic activity.

Though I had no idea at the time that I would end up writing a book on the subject, that encounter with Baudelaire’s prose poetry led me to embark on doctoral research about how later French modernist authors such as Stéphane Mallarmé, Guillaume Apollinaire, and Marcel Proust interacted with the press. Mallarmé and Proust have a reputation for being remote, esoteric authors who cut themselves off from journalism and other forms of what was dubbed “industrial literature”.

I found that they were actually fascinated by the press and eager to harness its power to their own creative ends. That insight yielded the idea that central figures in French modernism were “hustlers in the ivory tower”—at once devoted to artistic independence (the original meaning of “ivory tower”) and determined to carve out a space for their writing within the literary-journalistic marketplace.

What are the book's main ideas?

Hustlers in the Ivory Tower shows how French modernist writers including Mallarmé, Apollinaire, and Proust used newspapers and magazines as a “literary laboratory”, publishing works of poetry and imaginative prose in their pages, using their contacts to orchestrate publicity, and even paying bribes for puff pieces.

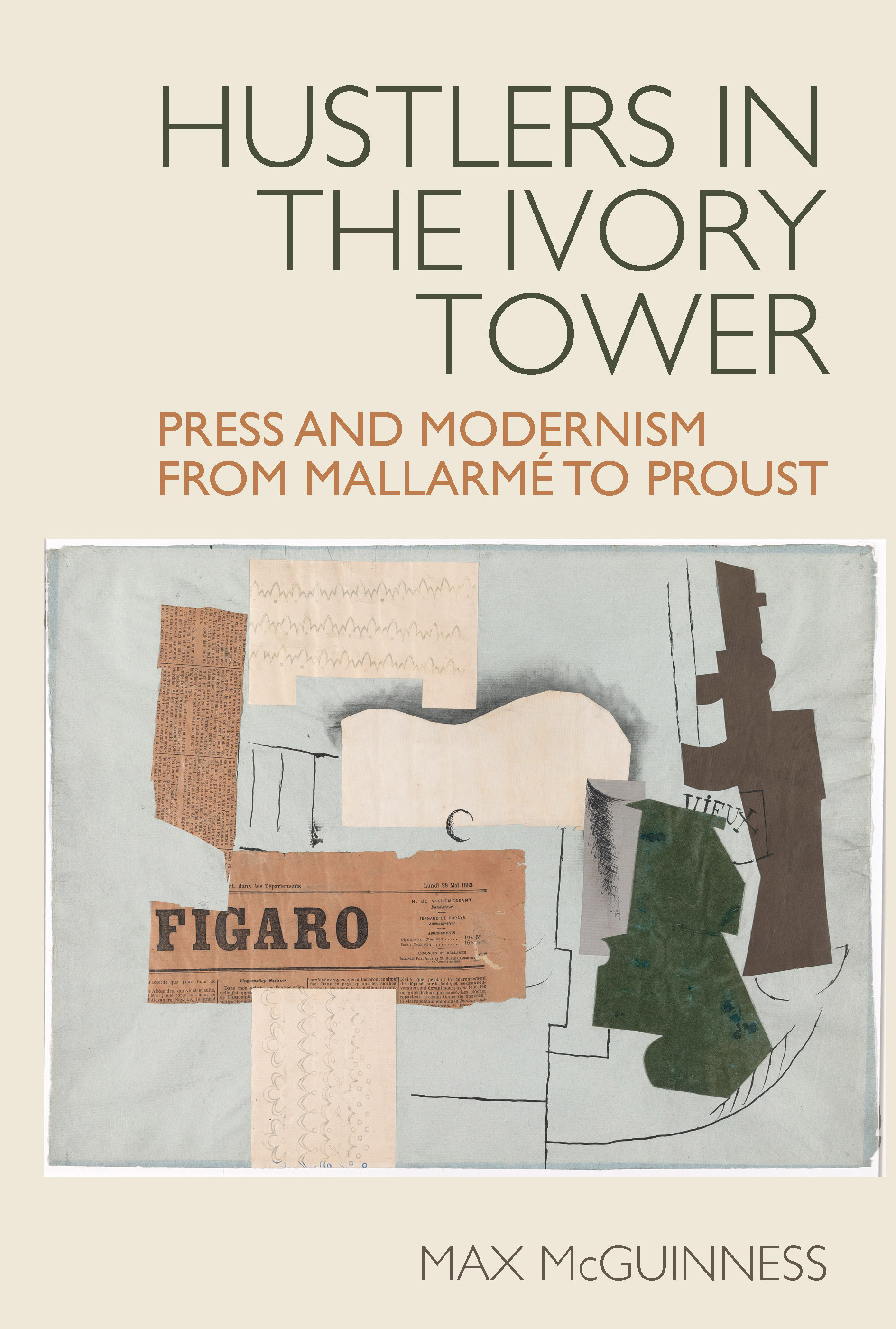

![]()

The book looks behind the scenes at the wrangling and wheeling-dealing between authors, editors, and publishers that drove the rise of modernist literature in France.

Those interactions with the press yielded nuanced, self-conscious portrayals of the tensions between journalism and literature in works of modernist poetry and prose that confront their own journalistic hinterland in unprecedented depth.

Whereas realist and naturalist writers, such as Honoré de Balzac and Guy de Maupassant, consistently demonized the press in their novels of journalism, their modernist successors pivoted between antipathy and enthusiasm for what Mallarmé dubbed “universal reportage”.

At once a model and a foil, the newspaper emerges in Hustlers in the Ivory Tower as the locus of French literature’s broader struggle to come to terms with modernity. The book also explores how writers today can learn from the French modernists’ tussles with the press as they struggle to create a space for their work in a world where writing and reading increasingly take place on screens.

Did you start out with the intention of writing a book about a particular topic, or did a book begin to make sense as you were researching?

My focus was always on press and literature during the modernist period. However, my work’s theoretical orientation changed markedly as I developed my research. I was initially guided by the ideas of the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu about “literary autonomy”. According to Bourdieu, French writers achieved autonomy—meaning independence from external forces such as the state, religion, and the market—in part by defining themselves against journalism and refusing to write for the mass press. My hypothesis was that that supposed rejection must nonetheless have left some traces on the work of French modernist writers.

As I spent more time reading newspapers and magazines from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, I found that Bourdieu’s model did not correspond to the reality of literary-journalistic life during the period. French modernist writers continued to publish works of poetry and imaginative prose in the mass press long after Bourdieu posits that they had repudiated journalism as the enemy of artistic independence. Some of them also became fascinated by the aesthetics of journalism. Mallarmé even celebrated the newspaper as the site of a nascent poetic revolution.

These findings meant that research originally conceived as a continuation of Bourdieu’s work evolved into a book offering an extensive critique of his model of literary autonomy (which has influenced other recent scholarship about press and literature in nineteenth-century France).

What did writing a book allow you to do that wouldn’t have been possible in another medium eg. journal article?

Hustlers in the Ivory Tower covers four decades of French literary history, spanning the 1880s to the 1920s. While Mallarmé, Apollinaire, and Proust are the central figures, the book features dozens of other authors, including Remy de Gourmont, Jules Renard, Édouard Dujardin, Alfred Jarry, Charles Péguy, Valery Larbaud, André Gide, Blaise Cendrars, Colette, and Alain. Editors and publishers such as Bernard Grasset, Gaston Gallimard, and Jacques Rivière also play a major role in Hustlers. Writing a book allowed me to trace connections between these figures and tell their story on a broad canvas.

Literary history is about far more than the small number of works that are passed down to posterity. In Hustlers in the Ivory Tower, I try to capture how the collective, collaborative culture of journalism, involving many little-known but influential actors, underlay the canonical achievements of French modernism. That project was always going to be a book-length endeavour.

How did you decide which publisher to place the book with?

Liverpool University Press is the leading anglophone publisher in French Studies, which made it an obvious choice for Hustlers in the Ivory Tower. LUP had also recently published a book that examines connections between press and literature during the Franco-Prussian War, Colin Foss’s The Culture of War: Literature of the Siege of Paris 1870-1871, so I thought that would make them receptive to my proposal.

How long did it take to write?

I had already undertaken a lot of the research for Hustlers in the Ivory Tower during my PhD. After signing the contract with Liverpool University Press, it took around two years to complete the book.

Did you ever experience any moments of writer’s block? What did you do to overcome this?

I didn’t find writer’s block to be a problem, but it was often difficult to find time to work on the book due to teaching commitments, having no contractual research time or leave, and having to move between three different universities on fixed-term contracts. The publisher’s deadline supplied essential discipline and motivation. My own experience of writing to deadline as a journalist also helped me to get the book finished.

What advice would you give someone thinking about writing a book?

Writing, and more precisely, publishing a book itself involves a lot of hustle, starting with the proposal and ending with correcting proofs. Responding to readers’ reports, clearing permission and image requests, and figuring out the index all require considerable energy and time. It’s important to prepare yourself for all these invisible yet essential aspects of writing a book.

If you could go back in time and give yourself one piece of advice before you started writing, what would that be?

Mallarmé once wrote that “everything in this world exists to end up as a book”. But a single book must not include everything. My advice to myself would be to start thinking as early as possible about what can be left out.

Max McGuinness

Dr Max McGuinness is a Teaching Fellow in French at Trinity College Dublin and a theatre critic for The Financial Times. He has previously taught at University College Dublin, the University of Limerick, and Columbia University, where he received his PhD in 2019. His first book, Hustlers in the Ivory Tower: Press and Modernism from Mallarmé to Proust (Liverpool University Press, 2024), explores how French modernist writers, including Mallarmé, Apollinaire, and Proust, used the press as a literary laboratory. He is currently co-editing The Irish Proust, a volume of essays about connections between Proust and Ireland for Bloomsbury Academic. His other publications include articles for the Bulletin d’informations proustiennes, Dix-Neuf, French Studies Bulletin, and Paragraph.