New discoveries from the Trinity Centre for Ageing and Intellectual Disability

The data being gathered and analysed through the Trinity Centre for Ageing and Intellectual Disability (the Centre) shines a new light on ongoing systemic social and political discrimination in Ireland against people with intellectual disabilities (ID). It is only in recent years that people with ID have lived to an older age, which is largely due to improved care and the commitment of families and people with ID themselves to improve their lives. Despite these improvements, ongoing and systemic social and political discrimination continues to exist in Ireland against those with ID. Tragically, the average age of death of an individual with ID in Ireland remains 19 years younger than for the general population.

The data being gathered and analysed through the Trinity Centre for Ageing and Intellectual Disability (the Centre) shines a new light on ongoing systemic social and political discrimination in Ireland against people with intellectual disabilities (ID). It is only in recent years that people with ID have lived to an older age, which is largely due to improved care and the commitment of families and people with ID themselves to improve their lives. Despite these improvements, ongoing and systemic social and political discrimination continues to exist in Ireland against those with ID. Tragically, the average age of death of an individual with ID in Ireland remains 19 years younger than for the general population.

Sarah works with Professor of Ageing and Intellectual Disability and former Dean of Health Sciences, Professor Mary McCarron, in supporting researchers who are investigating health and social issues faced by older people with ID. Professor McCarron, who is an international expert in the field of ID, with particular interest in ageing, dementia and palliative care in this population, is the founder of the first longitudinal comparative study on ageing in persons with an intellectual disability – the Intellectual Disability Supplement to the Irish Longitudinal Study in Ageing (IDS-TILDA). The goal of this study, founded in 2007, is to map how the health and well-being of people with ID changes over time. By learning more about the health and lifestyles of people with ID, in comparison with the general population, researchers hope to identify how issues can be managed or mitigated to improve health outcomes. For her work in this area, Professor McCarron (pictured below) received the inaugural Health Research Board Impact Award in 2019.

The award recognises how her research has transformed the health, care and living environments for people ageing with ID. Advancing authentic public engagement and involvement, Professor McCarron was chosen for her excellent and rigorous research, along with numerous impacts, including working with people with ID, their families, carers and service providers to advance co-created research; improving health outcomes for people with ID; improving health and social care services for people with ID; informing policies at local, national and international levels; and building a research workforce with national and global significance across disciplines and sectors.

The award recognises how her research has transformed the health, care and living environments for people ageing with ID. Advancing authentic public engagement and involvement, Professor McCarron was chosen for her excellent and rigorous research, along with numerous impacts, including working with people with ID, their families, carers and service providers to advance co-created research; improving health outcomes for people with ID; improving health and social care services for people with ID; informing policies at local, national and international levels; and building a research workforce with national and global significance across disciplines and sectors.

In an agreement processed by Trinity Research and Innovation, Professor McCarron was recently awarded a consultancy contract with the HSE to create the first National Memory Service for people with an Intellectual Disability, opening in 2020. Professor McCarron is particularly interested in early detection of dementia in people with ID, and in understanding the best ways of caring for and supporting people as they grow older. Supported by the Government’s Dormant Accounts Fund and the National Dementia Office, the Memory Service will be located at Tallaght University Hospital and developed in partnership with the Daughters of Charity Disability Support Service and the Centre. Professor Sean Kennelly, Clinical Associate Professor in Medical Gerontology at Trinity, will serve as Clinical Director of the Memory Service.

The issue of dementia is particularly acute for those people with ID who have Down syndrome. For this group, the average age of onset for dementia is 52 years and the trajectory of risk for developing dementia is 88% at age 65. This can be compared with a 5-8% risk in the general population at age 60. Yet the health system in Ireland is not set up to assess cognitive impairment in people with ID or provide post-diagnostic supports. One reason for this, perhaps, is that in contemporary Ireland the method of quantifying success tends to focus on commercial gains and quantifiable profit, and those who are perceived as incapable of contributing to or engaging with this system may be deemed less worthy of investment and funding that could be better directed to more “productive” population groups. After all, it was only in 2015 that The Assisted Decision Making (Capacity) Legislation passed in the Dáil, repealing 144 years of the Lunacy Regulations Act.

“Our policies at all levels recognise personal responsibility for health and well-being”, says Sarah, “yet supports at the local level are largely missing to help people make better choices and this is especially true for people with ID. If we want people to make healthy choices, we need to make it easier to do that. We need to consider who isn’t included in the current conversations.”

The IDS-TILDA project proudly promotes a person-centred approach, in which individuals with ID are empowered to participate in their own care and life choices, and are encouraged to have an active contribution to Irish society – including research. The slogan to promote their work is “nothing about us, without us”, and Professor McCarron emphasises that we must assume that people can, rather than cannot, achieve what they wish to achieve.

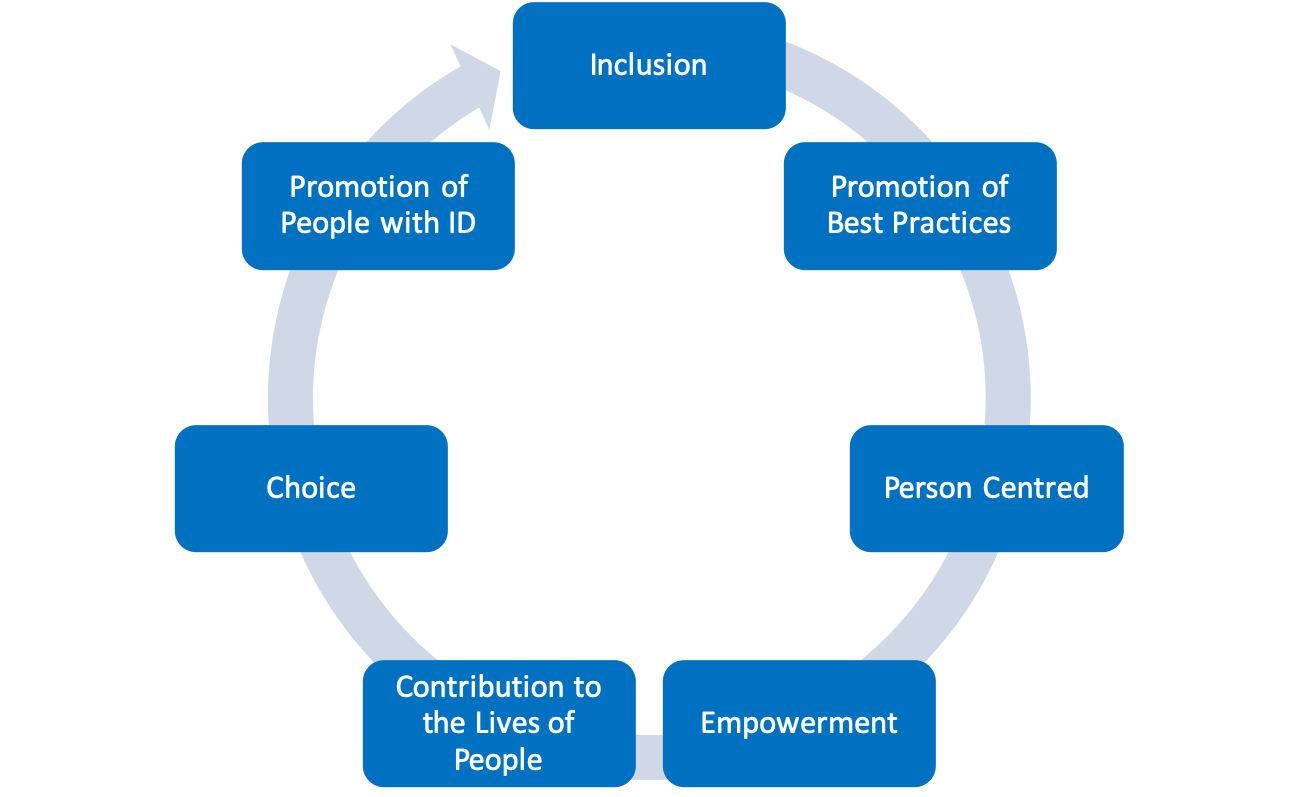

Below is the cycle employed by IDS-TILDA in order to promote the inclusion and empowerment of people with ID in Ireland. The IDS-TILDA study was an early adopter of a values framework, which is why it was also recognised as a national exemplar of public/patient involvement in research and included in the Horizon 2020-funded SPARKS Exhibition at Science Gallery Dublin.

As Sarah and I spoke, she highlighted the research of the Centre which has revealed levels of anxiety and depression among people with ID, who also often lack awareness about healthy eating, recommended amounts of daily exercise, the importance of friendships and life-long learning, and the implications of body weight. This is under-lined by IDS-TILDA data which has found that almost 80% of people with ID reviewed were overweight, but almost 64% thought they were the correct weight.

Furthermore – and this was the “blow your mind” part – Sarah revealed that 29% of IDS-TILDA study participants have no teeth. Despite seeing dentists more regularly than the general population, the reaction to a troublesome tooth is often just to pull it. Dentures can be unsuitable or inappropriate for some individuals to use or maintain, and there is not enough government funding or follow-up care for patients to receive implants. So many people are left with few or no teeth, effectively becoming orally disabled. Of the 29% of IDS-TILDA participants with no teeth, 68% had never received any sort of prosthetic device. In Ireland, people with intellectual disabilities are twice as likely to lose all of their teeth compared with the general population and twelve times as likely to become orally disabled by having neither teeth nor replacements such as dentures. “The population who are regularly seeing dentists are having some of the worst outcomes. Why is this?” Sarah asks, “And what can we learn about the delivery of services to this population in Ireland in order to improve service-delivery for all?”

Frequently, liquidised diets are seen as the solution to poor oral health but they often lead to further digestive problems, and potentially more medications. This brings us to the broader issue of drugs frequently being used to patch over the problem, rather than tackling wider (and more political) systems and structures. An emphasis on pharmacological approaches to health issues is common and IDS-TILDA data shows 95% of participants taking medicines and almost one quarter taking ten or more medicines each day to manage various health issues.

While advertising campaigns and consciousness-raising about health and well-being are targeted towards the general population, individuals with ID are mostly forgotten. An ingrained systemic issue is the assumption of the individual with ID’s inability to engage in healthy behaviours, and the idea that it is not worth the investment of time or money in their education about this.

On a positive note, Sarah states: “It’s interesting how well and how quickly researchers identify opportunities to translate research through partnerships with policymakers, advocacy organisation, service providers and service users – and this spans the entire research life-cycle – making it much easier to advance evidence-informed solutions. Some researchers tip into engagement efforts quite easily and work across sectors – with industry, academia, government, advocacy organisations, patient representative groups, charities and families – to solve a problem, provide opportunities or improve quality of life.”

One example of this is the Physical Activity Leader Project (P-PALs), led by Dr Mary-Ann O’Donovan, which prompts older adults with ID to take a leadership role in promoting physical activity amongst their peers. Based on Age & Opportunity’s Go for Life model, P-PALs is a joint project between the Centre, Age & Opportunity and the University of Barcelona. Funded by the European Union’s EIT-Health programme, the project co-designed easy read training material with people with intellectual disabilities to ensure that training sessions and materials used were accessible, effective and useful, while still keeping the fun and spirit of the Go for Life model. P-PALs developed the skills and confidence needed to lead weekly sports and activity sessions. This saw participants take charge of activity sessions for their friends, their peers and staff in order to get everyone more active. It has now been awarded phase-two funding through EIT-Health to continue to develop the programme.

Another focus of IDS-TILDA is to educate healthcare professionals on communicating with people with ID and developing better methods of health assessment. Led by Dr Eilish Burke, IDS-TILDA has developed a Massive Open Online Course to educate healthcare workers on health assessments for people with ID, and feedback has been positive: 87% of respondents to a survey reported that they had changed their practice as a result of the course and 83% said they had changed their perceptions of communicating with people with an intellectual disability.

According to Sarah: “There’s so much happening at this frontier, where lived experience and professional enquiry meet. There’s tremendous energy and a desire for evidence-informed policies, practices and services, nationally and internationally. In an era of fake news and pseudo-science, people seek reliable, trustworthy information and rigorous scholarship. They look to the world’s longest-standing and respected educational institutions, including Trinity College for quality assurance.”

Sarah pointed out that research into changes in health for people with ID are also beneficial for the general population. For example, researchers want to know why people with Down syndrome are less likely to get cancer or have hypertension, despite the fact that their BMI is often high, their diet regularly includes sugars and hydrogenised fats, and they tend to lead more sedentary lifestyles. Another focus of research is Alzheimer’s disease. This currently appears inevitable for people with Down syndrome and is linked to the presence of an additional copy of chromosome 21 which produces amyloid precursor proteins found in the brain in Alzheimer’s patients. Studying chromosomal differences can generate data that helps in finding treatments for the benefit of the entire population.

One of the main aims of the Centre is to encourage a shift in core values in Irish society so that it is easier for an individual to be an engaged citizen. Many people with ID have impressive creative skills, and can add significant cultural value if given the opportunity. Perceiving people with ID as incapable removes the need for social change. The Centre encourages the challenging of stereotypes, and a broader critical perspective on strategic decision-making and governmental policy development. “The invisibility is not okay,” Sarah says. “We need one another to be successful if we’re to tackle the societal challenges around us. We must preference collaborative, creative and inclusive approaches to problem-solving.”

Article by Dr Kate Smyth, Consultancy Development Officer, CONSULT Trinity, Trinity Research and Innovation.

For more information on academic consultancy: https://www.tcd.ie/innovation/consult/

Find out more about writing for researchMATTERS here.